I have a big interest in education, and I think we all do. We have a huge vested interest in it, partly because it’s education that’s meant to take us into this future that we can’t grasp. If you think of it, children starting school this year will be retiring in 2065. Nobody has a clue what the world will look like in five years’ time, yet we’re meant to educate them for it. Children have extraordinary capacities for innovation and all kids have tremendous talents but we squander them, pretty ruthlessly. I believe that creativity now is as important in education as literacy, and we should treat it with the same status.

I heard a story about a little girl who was in a drawing lesson. She was six and she was at the back, and the teacher said this little girl hardly ever paid attention, and in this drawing lesson she did. The teacher was fascinated and she went over to her and she said, “What are you drawing?” And the girl said, “I’m drawing a picture of God.” And the teacher said, “But nobody knows what God looks like.” And the girl said, “They will in a minute.”

My son was in the Nativity play at school. When the three boys came in bearing gifts they put these boxes down, and the first boy said, “I bring you gold.” And the second boy said, “I bring you myrrh.” And the third boy said, “Frank sent this.”

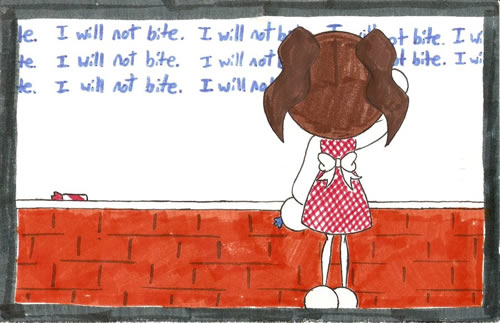

What these things have in common is that kids will take a chance. If they don’t know, they’ll have a go. They’re not frightened of being wrong and if you’re not prepared to be wrong, you’ll never come up with anything original. By the time they get to be adults, most kids have lost that capacity. They have become frightened of being wrong. We’re now running national education systems where mistakes are the worst thing you can make. The result is that we are educating people out of their creative capacities. Picasso once said this –he said that all children are born artists. The problem is to remain an artist as we grow up.

Every education system on earth has the same hierarchy of subjects. At the top are mathematics and languages, then the humanities, and the bottom are the arts. And in pretty much every system too, there’s a hierarchy within the arts. Art and music are normally given a higher status in schools than drama and dance.

Now our education system is predicated on the idea of academic ability as the whole system was invented to meet the needs of industrialism. So the hierarchy is rooted on two ideas; academic ability, and that the most useful subjects for work are at the top. The whole system of public education around the world is a protracted process of university entrance. The consequence is that many highly talented, brilliant, creative people think they’re not, because the thing they were good at at school wasn’t valued, or was actually stigmatized.

In the next 30 years, according to UNESCO, more people worldwide will be graduating through education than since the beginning of history. More people, and it’s the combination of technology and its transformation effect on work, demography and the huge explosion in population. Suddenly, degrees aren’t worth anything. Kids with degrees now struggle because you need an MA where the previous job required a BA, and now you need a PhD for the other. It’s a process of academic inflation. And it indicates the whole structure of education is shifting beneath our feet. We need to radically rethink our view of intelligence.

We know three things about intelligence. One, it’s diverse. We think about the world in all the ways that we experience it. We think visually, we think in sound, we think kinesthetically. We think in abstract terms, we think in movement. Secondly, intelligence is dynamic. If you look at the interactions of a human brain, intelligence is wonderfully interactive. The brain isn’t divided into compartments. In fact, creativity more often than not comes about through the interaction of different disciplinary ways of seeing things. Thirdly, intelligence is distinct.

I had a conversation with Gillian Lynne, a choreographer about how she became a dancer. She said that when she was at school, she was really hopeless. And the school, in the ’30s, wrote to her parents and said, “We think Gillian has a learning disorder.” She couldn’t concentrate; she was fidgeting, now they’d probably say she had ADHD. She went to see a specialist about her problems. The doctor went and sat next to Gillian and said, “Gillian, I’ve listened to all these things that your mother’s told me, and I need to speak to her privately.” He said, “Wait here. We’ll be back; we won’t be very long,” and they went and left her. As they left the room, he turned on the radio. When they got out the room, he said to her mother, “Just stand and watch her.” And the minute they left the room she was on her feet, moving to the music. And they watched for a few minutes and he turned to her mother and said, “Mrs. Lynne, Gillian isn’t sick; she’s a dancer. Take her to a dance school.” She went on to be very successful and is now a multi-millionaire.

I believe our only hope for the future is to adopt a new conception of human ecology, one in which we start to reconstitute our conception of the richness of human capacity. We have to rethink the fundamental principles on which we’re educating our children to secure a better future for them.

———

This is a summary of a tedtalk.

Listen to the talk: www.ted.com/talks/ken_robinson_says_schools_kill_creativity

Have something to say? Comment on it at the bottom of the article.

This talk has been summarized by Robyn Darbyshire

Leave a Reply